Every transaction you make tells a story. Where you shop, what you buy, when you’re broke, when you’re flush. Your bank knows when you gamble, when you’re pregnant before you tell anyone, when you’re job hunting, and when your marriage is falling apart based on therapy and legal consultations showing up in your account.

And in 2026, they’re monetizing every byte of it.

Here’s the part nobody’s saying out loud: the privacy laws protecting your health records, your search history, and your social media don’t apply to your financial data. Banks got carved out of nearly every state privacy law passed in the last five years.

Translation: your bank can build an advertising empire with your transaction data, and the privacy regulations everyone’s celebrating? They don’t touch it.

The Loophole Nobody Talks About

Twenty states now have comprehensive privacy laws. California’s CCPA, Colorado’s CPA, Virginia’s VCDPA—they all give consumers rights to access, delete, and opt out of data sales.

Except when it comes to financial institutions.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s own report confirms it: “Many new state data privacy protections exempt financial institutions and consumer financial data covered by federal law, even though states generally have authority to go beyond the federal rules.”

The federal law they’re referring to? The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act from 1999. It was written before smartphones existed, before Venmo, before anyone imagined banks would compete with Google for ad revenue.

GLBA requires banks to send you a privacy notice—that document you’ve never read—and lets you “opt out” of some data sharing. But here’s the trap: banks can use your data internally for “their own purposes” without your consent. And when they share it with “affiliates,” the opt-out doesn’t apply either.

The result? Your financial data has weaker privacy protections than your Instagram likes.

What “Monetizing Financial Data” Actually Means

Let’s be specific about what banks are building.

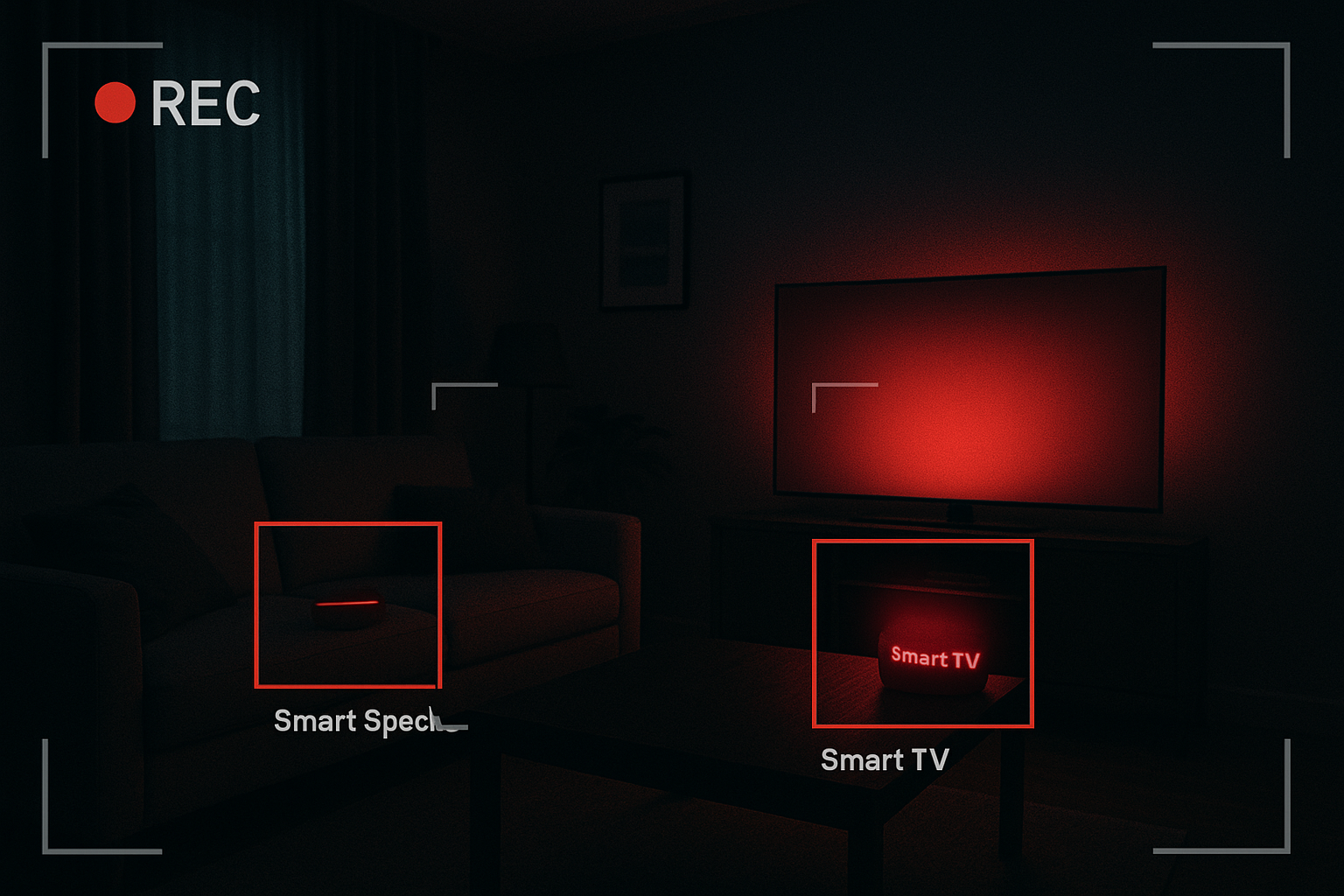

Chase Media Solutions launched in 2023. It lets advertisers target Chase customers based on their spending patterns. Bought dog food on a Chase card? Petco can now show you ads. Booked a hotel? Expedia gets access. This isn’t hypothetical—it’s live, right now.

Bank of America has been building advertising products for years. They anonymize and aggregate transaction data, then sell insights to brands about where customers shop and how much they spend.

Wells Fargo has a media network. So does Capital One.

The pitch to advertisers is simple: “We know what your customers actually buy, not just what they click on. We can prove ROI because we see the transaction.”

And technically, they’re not “selling your data.” They’re selling “advertising access” to people who match your spending profile. The legal distinction matters. The practical outcome doesn’t.

The CFPB’s Half-Solution That Changes Everything (And Nothing)

In October 2024, the CFPB finalized its “Personal Financial Data Rights” rule under Section 1033 of Dodd-Frank. It’s the most significant update to financial data rights in 14 years.

The good news: You can now demand your bank transfer your financial data to competitors for free. Want to switch from Chase to Ally? You don’t have to manually download 12 months of statements anymore. The bank has to hand it over.

The not-so-good news: This makes your data more portable, not more private.

The rule requires banks to share data with third parties you authorize—fintechs, budgeting apps, competing banks. But it doesn’t restrict what those third parties do with the data afterward. And it definitely doesn’t stop banks from using your data for internal advertising operations.

The compliance timeline:

- April 1, 2026: Largest banks must comply

- April 1, 2027-2030: Phased rollout for smaller institutions

So by 2026, your financial data becomes easier to move, which is great for switching banks. But the surveillance economy around that data? Untouched.

The Privacy-Enhancing Technologies That Won’t Save You

You’ll hear a lot about “Privacy-Enhancing Technologies” (PETs) in 2026. Cryptographic techniques that let companies analyze data without seeing individual records. Differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, secure multi-party computation.

The global PET market is projected to hit $12-28 billion by 2030, with banking and financial services accounting for 27.9% of adoption.

Sounds promising. Except PETs don’t prevent data collection—they just add encryption steps to analysis.

Your bank still knows you spent $347 at a fertility clinic. They still see the $1,200/month therapy bills. They still track every DoorDash order and Tinder subscription. PETs just let them analyze that data without technically “identifying” you in the aggregate reports they sell.

It’s privacy theater at scale.

The Real Problem: Consent Mode Is a Joke

Google’s “Consent Mode v2” became the standard in 2026. It’s the framework websites and apps use to ask permission before tracking you with cookies.

Financial institutions adopted it. But here’s what consent looks like in practice:

“We use your data to improve your experience, provide personalized services, and offer relevant offers. Do you consent?”

- Yes

- Manage Preferences (which takes 17 clicks to find the actual opt-out)

And even if you click “No,” the bank can still use your transaction data for their own “business purposes” under GLBA. Your refusal changes almost nothing.

This is why 84% of consumers fear AI in banking according to RFI Global’s research, yet adoption continues anyway. The consent is performative.

Why Your Data Broker Removal Service Misses This Entirely

You’ve probably seen the ads: “Remove your data from 180+ data brokers!” Services like DeleteMe, Incogni, and Privacy Bee that scrub your info from people-search sites.

They don’t touch financial data. They can’t. Those brokers don’t have access to your bank transactions (usually). But your bank does, and they’re not legally considered a “data broker” under most state laws.

So you can spend $200/year removing your name from Spokeo and Whitepages, but Chase still knows you spent $3,400 at a casino last month and is feeding that insight to their advertising clients. If you haven’t already tackled the basics, start with understanding how to remove your data from the internet, but know that financial privacy requires a completely different playbook.

What You Can Actually Do (And What You Can’t)

Let’s separate the actionable from the futile.

Things that might help:

1. Opt out of everything the bank legally has to let you opt out of

Log into your bank’s privacy settings. Find the section on “sharing with affiliates” and “sharing with third parties for marketing.” Opt out of everything.

Will this stop internal advertising? No. But it limits external sharing.

2. Use cash for sensitive purchases

Therapy, medical care, political donations, anything you don’t want analyzed—pay cash. Yes, it’s inconvenient. That’s the price of privacy in 2026.

3. Separate your financial identities

One checking account for recurring bills. One credit card for discretionary spending. Makes behavioral profiling harder because the data’s split across institutions.

4. Read the actual privacy notice

Not the 47-page legal document. The “short form” privacy notice banks are required to provide. It tells you exactly who they share with and whether you can opt out.

Things that won’t work:

1. Expecting the law to protect you

State privacy laws exempt financial institutions. Federal law (GLBA) is 25 years old. It won’t change in 2026.

2. Trusting “anonymized” claims

When your bank says they “anonymize” data before sharing, they mean they remove your name. But transaction patterns are unique enough to re-identify individuals with 90% accuracy using just four data points. This isn’t privacy—it’s liability management.

3. Assuming fintech is better

Venmo, Cash App, Chime—they’re collecting the same data. Often with less regulatory oversight than traditional banks because they’re not technically “banks.”

The Business Model Is the Surveillance Model

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: modern banking is architected around data extraction.

Your checking account costs the bank money to maintain. They need to extract value elsewhere. Option one: charge fees (unpopular). Option two: monetize your transaction data (invisible).

Banks chose option two.

And because 27.9% of all privacy-enhancing technology investment comes from financial services, they’re not abandoning surveillance—they’re making it more compliant.

The goal isn’t to stop tracking you. It’s to track you in a way that survives regulatory audits.

The 2026 Landscape: Compliance Without Privacy

By the end of 2026, here’s what will have changed:

- Banks will let you port your data to competitors more easily (Section 1033 compliance)

- Privacy-enhancing technologies will be standard (making surveillance harder to detect)

- More banks will have formalized advertising divisions (monetizing the data they already collected)

- State privacy laws still won’t apply to financial institutions (GLBA carve-outs remain)

What won’t have changed: The fundamental business model of surveillance finance.

If you’re looking to protect yourself in other ways, understanding how subscription services drain your finances is equally important, as many recurring charges leave permanent data trails that banks analyze.

The Bottom Line

Your bank knows more about you than Google, Facebook, and Amazon combined. And unlike those companies, your bank is exempt from the privacy laws designed to give you control.

The CFPB’s new data portability rule makes switching banks easier. It doesn’t make banks less invasive.

Privacy-enhancing technologies make surveillance more compliant. They don’t make it stop.

And the state privacy laws everyone celebrates? They carved out exceptions for financial data.

In 2026, if you want financial privacy, you have exactly two options: pay cash for everything, or accept that your transaction history is a product your bank sells to the highest bidder.

Most people will choose convenience. Banks are counting on it.

Join The Global Frame

Get my weekly breakdown of AI systems, wealth protocols, and the future of work. No noise.